Chrome Hearts at The Surfrider Malibu Hotel: A Darker Vision of Coastal Luxury

Inside Chrome Hearts’ $37.5 Million Malibu Hotel Takeover — The Surfrider, Richard Stark, and the Future of Luxury Hotels

There are brands that sell objects, and there are brands that construct entire philosophies around the act of possession. Chrome Hearts has always belonged emphatically to the latter category.

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

Founded in Los Angeles by Richard Stark in 1988 — originally as a leather goods company for motorcycle culture, though that origin story has long since been eclipsed by something far more complex — it has evolved into one of the most quietly sovereign luxury houses operating anywhere in the world. Sovereign in the truest sense: it answers to no conglomerate, distributes according to its own logic, and maintains a physical presence so deliberate that a Chrome Hearts boutique feels less like retail and more like an audience granted by appointment. The clientele, over the decades, has included everyone from Karl Lagerfeld to Rihanna, from Bella Hadid to the kind of serious collectors who understand that scarcity and intention are the only currencies that actually hold.

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

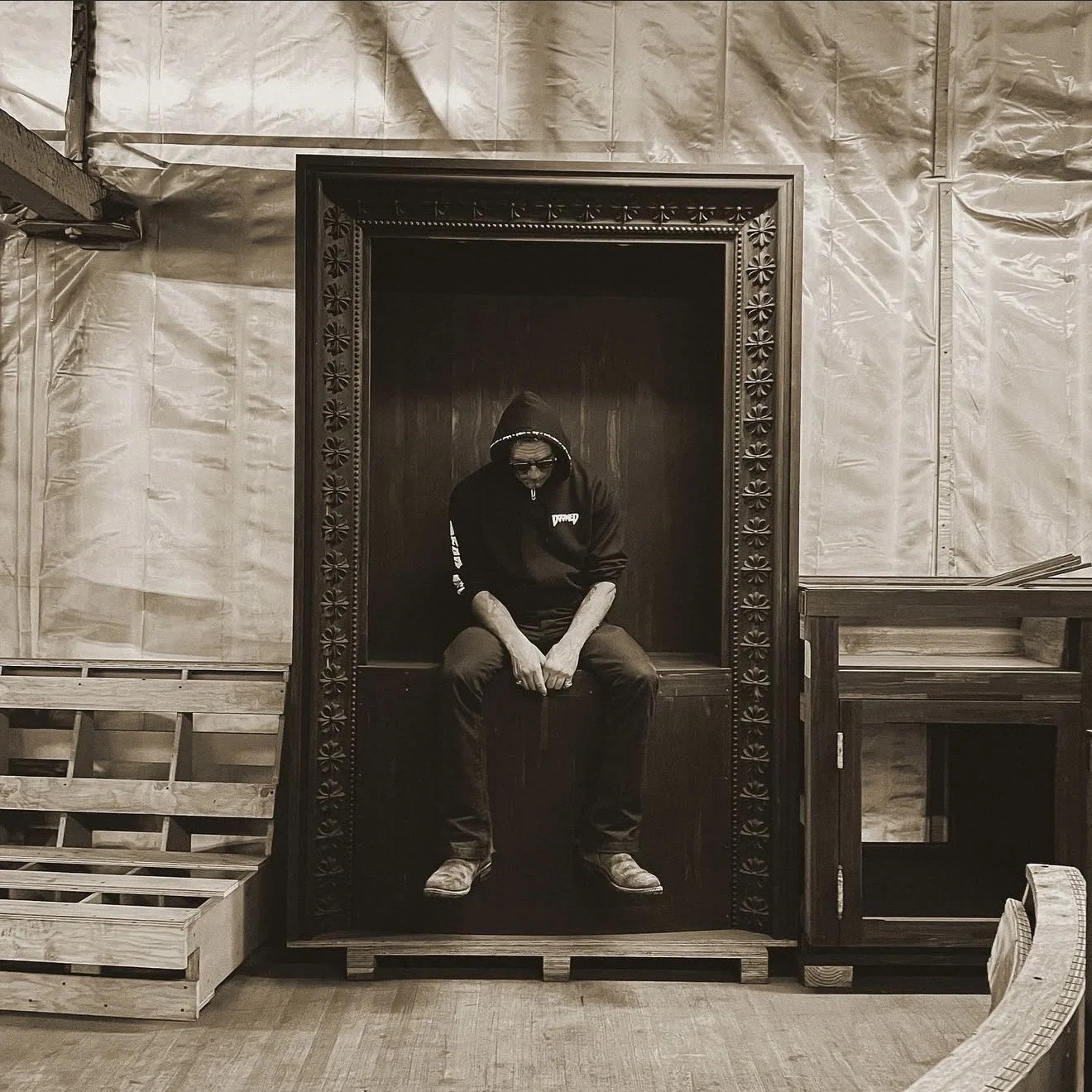

What Chrome Hearts has never been is a rock-and-roll brand that got lucky with celebrities. That reading has always missed the point. Stark built something far more architectural in sensibility — a house whose material language is rooted in sterling silver, heavyweight leather, handmade detailing, and a Gothic American vocabulary that feels genuinely authored rather than art-directed. Every piece, whether a ring worn to an industry dinner or a cross-inlaid cabinet placed in a modernist home, carries the same formal conviction. That consistency is rare. In an industry increasingly governed by creative cycling and quarterly repositioning, Chrome Hearts has remained, almost defiantly, itself.

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

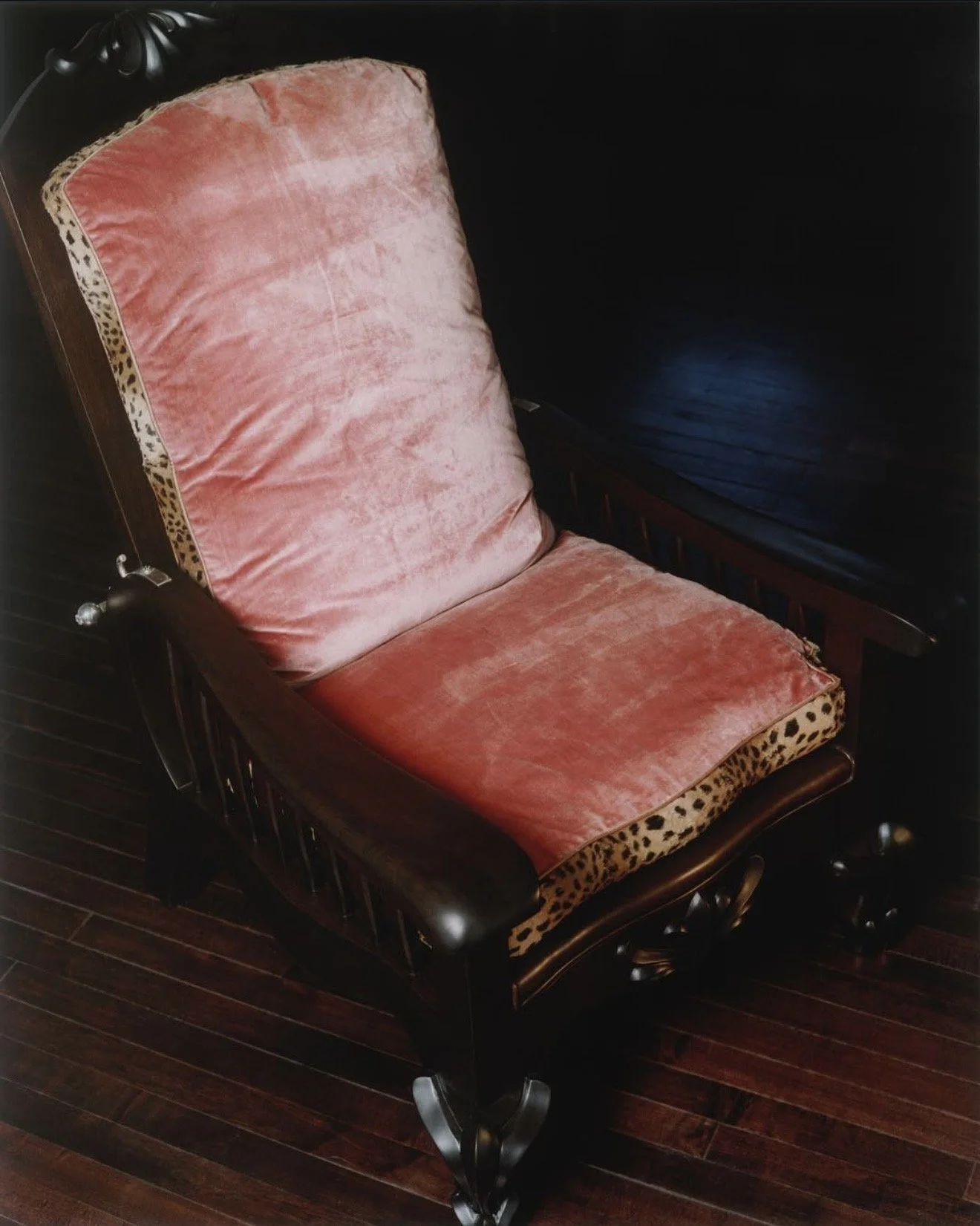

It is this authorship that explains its particular hold on a certain kind of design-conscious devotee. The brand’s expansion into furniture and interiors — exquisitely heavy tables, upholstered pieces with the same silverwork detailing found on its jewelry, objects that seem to carry genuine mass — was not a brand extension in any conventional sense. It was evidence that the world Chrome Hearts was building had always been three-dimensional. That collectors began furnishing rooms with the brand’s objects was not surprising to anyone who had ever spent time inside one of its boutiques and felt the specific atmosphere those spaces produce: dim, weighted, almost ecclesiastical in their commitment to material.

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

The Coast Before Chrome

Against that context, the acquisition of The Surfrider Malibu — the 20-room boutique hotel perched above the Pacific Coast Highway — for approximately $37.5 million in 2025 reads not as an ambitious leap but as an obvious next move. The world-building was always going to require physical space at a larger scale. A hotel is simply a boutique you can sleep in.

Photo courtesy of The Surfrider Hotel

The Surfrider has carried its own mythology along Malibu’s coast. An intimate property in a stretch of coastline defined by compound walls and private beach access, it has represented a particular mode of California hospitality — sun-bleached, architecturally restrained, operating on the kind of understated coastal confidence that Malibu has always projected to those fortunate enough to access it properly. Its scale kept it personal. Its location kept it aspirational. The aesthetic, in its existing form, has operated in the vocabulary of light: white walls, ocean air, the suggestion that luxury here means subtraction rather than addition.

Photo courtesy of The Surfrider Hotel

Darkness Facing the Pacific

Chrome Hearts works in the opposite register entirely. Its rooms — literal and figurative — are about depth and accumulation, about materials that develop patina and presence, about darkness used not for drama but for intimacy. The interesting question is not whether these two aesthetic languages are in tension, but what happens when someone with Stark’s material confidence enters a space defined by restraint and chooses what to keep. The reported intention to preserve the hotel’s intimate scale and to potentially collaborate with the Jean-Georges hospitality group suggests a sensibility that understands the Surfrider’s value is partly atmospheric and not easily replaced. That kind of restraint, in a brand known for maximum material commitment, is itself telling.

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

Where the Design Lives

One imagines what Chrome Hearts’ design language could do with a room that faces the ocean at dusk — the silver hardware on dark-stained wood, the leather against linen, the cross motifs somewhere between devotional and decorative, the whole thing feeling as if it had been assembled by someone with a private collection rather than a procurement team. Hospitality, at its most compelling, has always been about the imposition of a specific sensibility onto a shared space. The best hotel rooms feel like visiting someone’s interior life. Chrome Hearts has been building an interior life for decades.

Photo courtesy of Chrome Hearts

Fashion houses acquiring property is no longer an anomaly — Ralph Lauren has demonstrated what sustained aesthetic vision can do for a brand across categories, and Armani’s hotel in Milan has long been a case study in controlled atmosphere. But Chrome Hearts is neither of those. It is darker, stranger, more American in the best sense — less interested in European luxury codes than in something more handmade and more personal. Whatever the Surfrider becomes under its stewardship, it will not look like anything that already exists on the coast. That, perhaps, is sufficient.